This is the second and the last part of the series about the history of Firefly Zero. The first part: A brief history of fantasy video game consoles.

2017. WebAssembly

We already touched a bit on WebAssembly in the first part. It was released in 2017. I started to work with WebAssembly in 2019. At the time, the only thing I knew about it was that it’s a way to write frontend code in the Go programming language instead of JavaScript. And since JavaScript is somewhere at the bottom of my top of programming languages, that was enough of a reason for me to start using WebAssembly with Go.

One of the first things I did was create gweb. It’s a tool that makes it possible to do in Go everything you could do in JavaScript. I also made quite a few demos for it. My favorite one is Breakout, an improved port of the classic video game with the same name. You can click the link and play it right in your browser. But beware, it’s quite addictive.

The next benefit of WebAssembly I discovered, besides writing JavaScript-free frontend, is that you can run in the browser existing games and tools with almost no modifications. I started to make online playgrounds for my Python projects:

- svg.orsinium.dev: a playground for svg.py, a Python library for generating SVG images.

- wps.orsinium.dev: a playground for wemake-python-styleguide, a tool for finding bugs in Python code.

And some people were pushing it even further. Here are a few of my favorite browser ports:

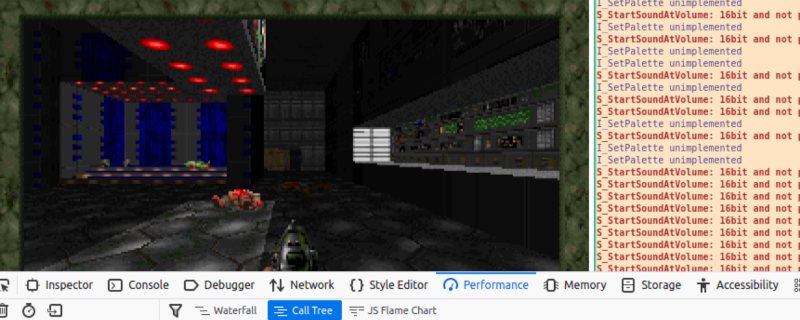

- DOOM

- Windows 95

- Gameboy (you’ll need a ROM to play, download one here)

2023-11. Aard

In November 2023, I started to write a programming language called Aard. Currently, it’s on pause in favor of Firefly Zero, so I have nothing to show but a lot to tell. It’s one of the very few languages that target only WebAssembly. Which means, it can use its full power without compromises. When it’s done, it will be a way to write the smallest and the fastest programs for WebAssembly, beating Rust, Zig, C, and other programming languages that are generally considered fast.

For me, Aard meant going back to WebAssembly. And this time, I had to know everything about it. I started reading all proposals and specifications, digging into different implementations, discovering best practices, etc. I learned that WebAssembly isn’t just a way to run Go in the browser. It’s much, much more than that!

- WebAssembly is a secure sandbox. WebAssembly apps can do only what their runtime allows them to do.

- It makes impossible some common errors that plague everything written in C. You cannot access memory you don’t own, you can’t get a random “garbage value” in a variable. If there’s a bug in your app and hackers can write any values into the memory, they still can’t modify how your app works.

- It’s a virtual machine. The runtime can observe a lot about the running app. It knows how many instructions the app executed, if it’s stuck in a loop, if it sends a network request, etc.

- It’s fast. Running a WebAssembly app is slower than running a native C app but much faster than running any interpreted language or any other virtual machine.

- It’s portable. The same WebAssembly app will work in exactly the same way in all environments.

- It’s relatively easy to implement. That means, there are lots of runtimes designed for different environments: browsers, smart contracts, embedded systems, etc.

2024-02. TinyGo

On 3 February 2024, I attended FOSDEM. It’s a free conference dedicated to all things open source. There are lots of amazing people, talks, and stickers. There I met Ron Evans, a core maintainer of TinyGo. TinyGo is a “Go compiler for small places”. It makes it possible to run almost any Go code on almost any device. The produced code is generally very small and quite fast. And it can compile Go to WebAssembly!

Word by word, I started to talk about Aard and WebAssembly. And turns out, that Ron had a talk planned for WASM/IO, a conference in March 2024 dedicated to WebAssembly. He had some ideas of what to show but nothing was implemented yet. So, we decided to work on it together. In just one month, we produced several cool projects with a common idea of fusing Go and WebAssembly:

- We added a pure WebAssembly target into TinyGo. That means, now you can run Go apps in non-browser WebAssembly runtimes.

- We made Wazero compile with TinyGo. Wazero is a pure Go runtime for WebAssembly. That means, now you have a WebAssembly runtime that can run on any device that TinyGo supports. And it’s a very long list! TinyGo-powered projects are running on keyboards, drones, thermometers, and even earrings.

- We made Mechanoid, a framework for running WebAssembly on IoT devices. It’s a TinyGo and Wazero-powered runtime that provides to WebAssembly apps access to things like device screen, sensor values, keyboard input, etc.

- We launched Mechanoid on Thumby, the smallest game console in the world.

Ron presented all of it and some Mechanoid-powered projects at WASM/IO. Here is the full talk: The Smallest Thing That Could Possibly Work: WASM on Microcontrollers With TinyGo.

2024-02. Gamgee

One more thing that I wanted to do a part of messing with WebAssembly is running WASM-4 (we talked about it in part 1) games on a small physical device. I picked Rust over Go as the best language for the job. Writing code in Rust is generally harder but the resulting apps consume less memory, which is important if I want to give the running games as much resources as possible. Also, Rust has the best ecosystem of everything related to WebAssembly.

So I picked the following tech stack:

- Rust as the programming language.

- Wasmi as the WebAssembly runtime. It is designed for constrained environments, exactly what I needed.

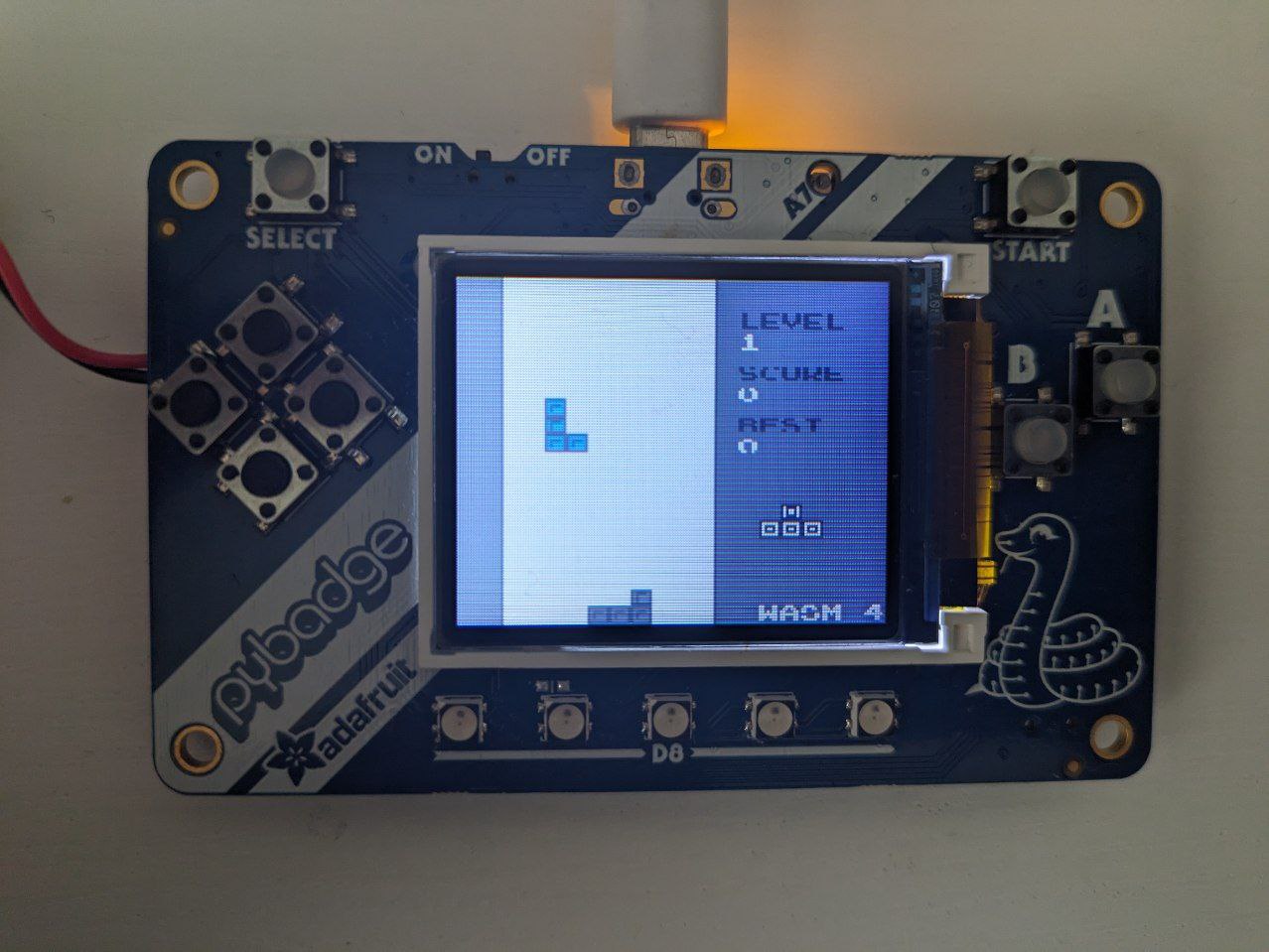

- AdaFruit PyBadge as the device. It has just about 196 KB of RAM, a small 180x148 TFT display, and just enough buttons for playing a retro game.

The result of it was gamgee, the world’s first game console running WebAssembly. And it works great! It doesn’t have sound because I didn’t have time to implement it but that was already enough for a proof of concept. I had proof that it is possible to make a game console running WebAssembly, and you need for it just a few kilobytes of RAM.

2024-03. Firefly Zero

On 10 March 2024, I met with Alex, told him about the same history as you just read, and said that I want to make a handheld game console with WebAssembly and multiplayer. The very next day we started to write the first documentation for what would later become Firefly Zero. I drafted some design ideas for graphics and Alex wrote down what hardware components we will need. This was the beginning.

At the moment of writing this post (July 2024), we already made a lot of progress, especially considering that we both have daily jobs and work on Firefly Zero on evenings and weekends. We have SDKs for Go and Rust, drafts for SDKs for Python, C, C++, Zig, and Elixir, very powerful CLI, online game catalog with one game, testing framework, cross-platform emulator, graphics, and even multiplayer. If we are pressed to release the project as-is at this very minute, we already wouldn’t be ashamed of the result. And yet, we still have a lot of things we want to implement before that. This is our first big project, and we want it to be very good and memorable.

The show must go on!